Este artículo está disponible sólo en inglés.

What happened to the small-cap premium?

Commentary by Andrew Shuman, Director of Research, Vanguard Oversight & Manager Search

Key points

- U.S. small-capitalization stocks have underperformed large-capitalization stocks for a decade, a reversal of the historical “small-cap premium.”

- Structural challenges—including weaker profitability, sector composition differences, and greater interest rate sensitivity—have weighed on small-cap performance.

- Despite those headwinds, valuation gaps suggest small-caps may offer long-term opportunities, especially for skilled active managers and factor-based strategies emphasizing quality and valuation.

U.S. small-caps have significantly underperformed their large-cap counterparts over the last decade. This is a reversal from what investors have come to expect since the 1990s, when seminal academic research argued for the existence of a “small-cap premium.”1 Although non-U.S. stocks—which have also lagged over the last decade—have enjoyed a resurgence in 2025, small-caps have continued to struggle despite their attractive valuations. Tariff concerns are at least partly to blame, as small-caps have historically been more cyclical and economically sensitive.

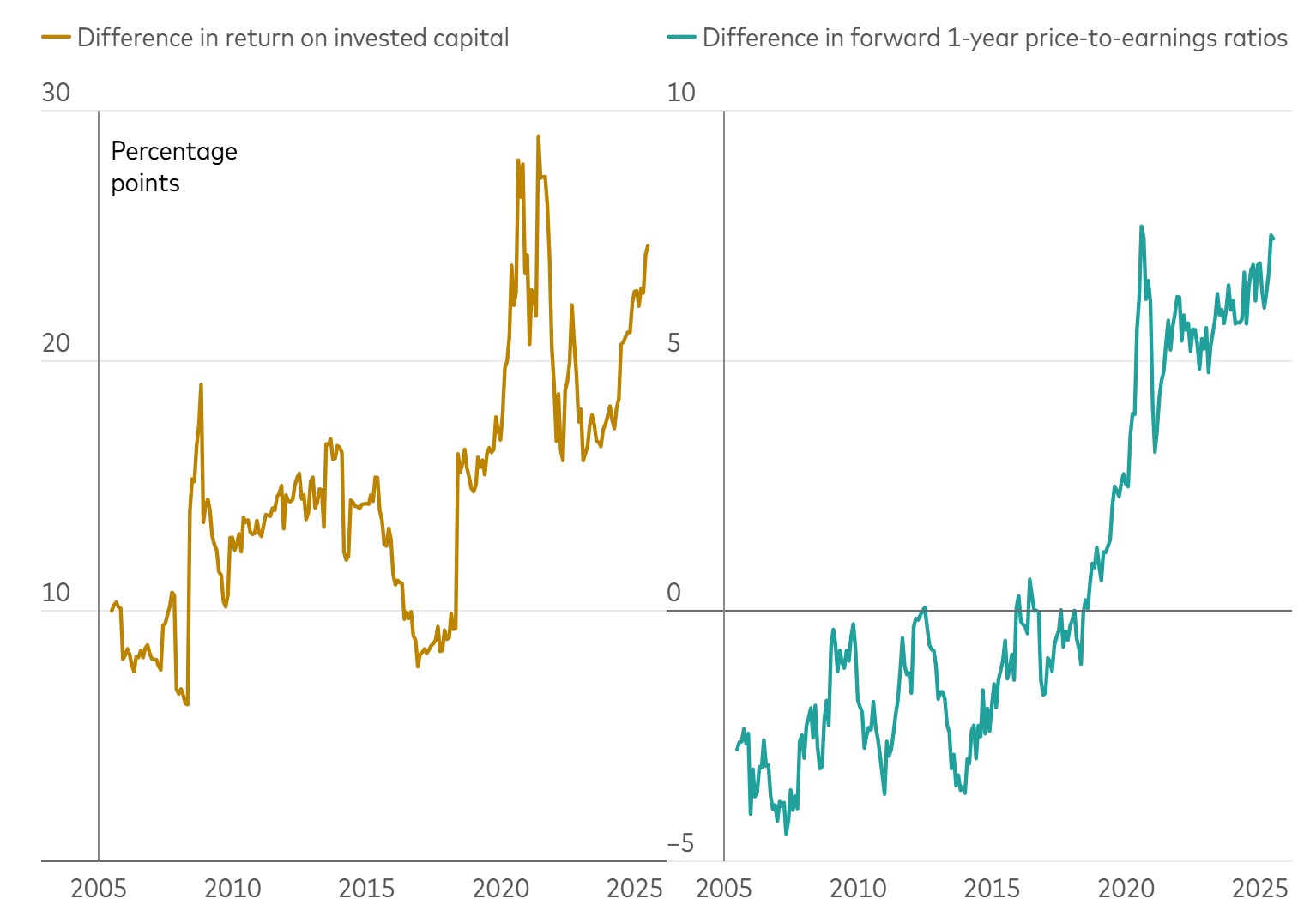

Our research, however, suggests that more structural factors may be at play. Smaller companies have deteriorated in quality compared with large-caps, as the figure below shows. Through July, almost a third of the companies in the Russell 2000 Index were loss-making based on annual earnings per share. Much of large-caps’ vaunted valuation premium appears at least partly justified by their superior profitability.

Large-caps have outpaced small-caps in profitability and valuations

Notes: The difference in return on invested capital is calculated using the weighted average return on invested capital measured in percent for stocks in the Russell 1000 Index minus the same metric for stocks in the Russell 2000 Index. The difference in forward 1-year price-to-earnings ratios is calculated using the weighted harmonic average price-to-earnings ratio of stocks in the Russell 1000 Index, based on consensus earnings per share estimates for the next fiscal year, minus the same metric for stocks in the Russell 2000 Index.

Sources: Vanguard calculations using data from FactSet, from July 2005 through July 2025.

The initial public offering (IPO) market also appears to have played a part in small-caps’ underperformance. Although hundreds of young, promising small-cap companies have gone public in the past, many are now staying private for longer and going public at large-cap levels, if at all. This has led to the composition of the public small-cap universe becoming older over time. Additionally, the companies that have gone public over the last 10 years have tended to be less profitable than in prior decades.

Structural disadvantages and sector gaps are weighing on small-caps

The historic outperformance of mega-cap technology stocks, often referred to as the “Magnificent Seven,” has played a role in the divergence between large- and small-caps. These stocks (Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta Platforms, and Tesla) have accounted for half of large-caps’ annualized outperformance of around 6 percentage points over the last 10 years. Differences in sector composition between large- and small-caps have also been a driver—tech stocks comprise 37% of the Russell 1000 but just 12% of the Russell 2000.

The increase in interest rates over the last few years has weighed disproportionately on small-caps. While larger-cap companies were able to lock in low rates on very long-term debt when rates were lower, many small-cap companies with short-term debt structures have had to roll over their debt at higher interest rate levels. This has led to an increase in the percentage of small-caps with an interest coverage ratio (operating income divided by interest expense) of less than 2, a level generally considered safe as it means a company is earning at least twice what it needs to cover its interest payments.

Against this challenging backdrop, active small-cap fund managers have fared much better than their large-cap counterparts.2 Actively managed small-cap funds tend to have a quality bias, with underweights to loss-making companies, which has been a consistent tailwind for them.

“The question now: Has repricing gone too far, with expectations for small-caps too bearish and those for large-caps too lofty?”

Andrew Shuman, Director of Research, Vanguard Oversight & Manager Search

Where to from here?

The decline in small-cap valuations has been warranted, arguably, by their decline in quality. The question now is whether the repricing has gone too far, with expectations for small-caps too bearish and those for large-caps too lofty. Looking at the price-to-earnings data another way, even when limiting the universe to “quality” companies (those with returns on invested capital of more than 20%), small-cap stocks appear very cheap compared with large-caps of comparable profitability.

Quality small-caps have become cheap compared with large-caps

Notes: The difference in forward 1-year price-to-earnings ratios is calculated using the weighted harmonic average price-to-earnings ratio of quality small-cap stocks, based on consensus earnings per share estimates for the next fiscal year, minus the same metric for quality large-cap stocks. Quality stocks are defined as those with average returns on invested capital of more than 20% over the trailing three years. Small-cap stocks refers to those in the bottom third of the Russell 3000 Index by market weight and large-caps refers to those in the top third of the Russell 3000 Index by market weight.

Sources: Vanguard calculations using data from FactSet, from July 2005 through July 2025.

Our capital markets forecasts suggest that valuation differences have indeed grown too wide. We expect small-caps to outpace large-caps by an annualized 1.9 percentage points over the next decade. However, some caution is warranted given the prevalence of small-cap companies with weak profitability and risky balance sheets. Investors may want to consider low-cost active funds where skilled managers can be selective or funds employing factor-based strategies emphasizing quality and valuation.

[1] Eugene F. Fama and Kenneth R. French. Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 33, No. 1, February 1993, pp. 3–56.

[2] According to Morningstar’s U.S. Active/Passive Barometer Report: Midyear 2025, only 5.8% of active large-cap blend funds beat their benchmarks after fees over the last 10 years, compared with 18% for small-cap blend funds and 36% for small-cap growth funds.

Notes:

All investing is subject to risk, including the loss of the money you invest.

Investments in stocks issued by non-U.S. companies are subject to risks including country/regional risk and currency risk.

Prices of mid- and small-cap stocks often fluctuate more than those of large-company stocks.

Data provided by Morningstar is property of Morningstar and Morningstar’s data providers and it should therefore not be copied or distributed. Morningstar and its data providers are not responsible for any certification or representation with respect to data validity, certainty, or accuracy and are therefore not responsible for any losses derived from the use of such information.

Vanguard Mexico is not responsible for and does not prepare, edit, or endorse the content, advertising, products, or other materials on or available from any website owned or operated by a third party that may be linked to this email/document via hyperlink. The fact that Vanguard Mexico has provided a link to a third party's website does not constitute an implicit or explicit endorsement, authorization, sponsorship, or affiliation by Vanguard with respect to such website, its content, its owners, providers, or services. You shall use any such third-party content at your own risk and Vanguard Mexico is not liable for any loss or damage that you may suffer by using third party websites or any content, advertising, products, or other materials in connection therewith.